By Sura Khuzai

Founder Basira Initiative

It all started with my children’s outgrown toys and clothes; we found ourselves surrounded by things we had bought and used, packed, put away, moved from here to there, storing them into a closet, a bag, a shelf, until the time to move them came again.

We then realised that we had to make difficult decisions, to downsize the things that stirred up fond memories and brought smiles to our faces.

And this is how our story began…

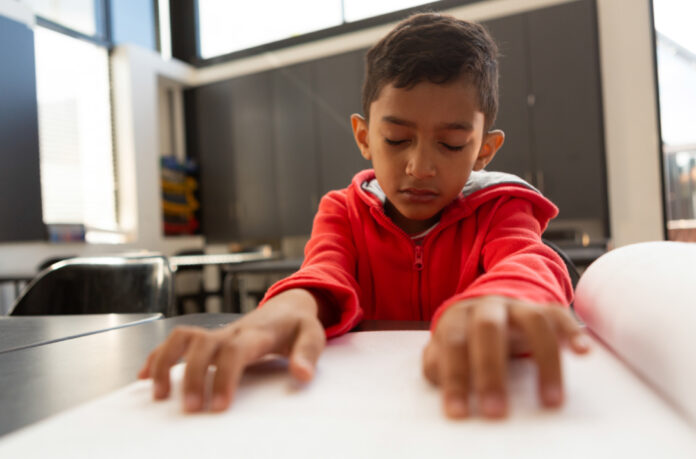

Seeing as a blind person

After searching for the right organisation to benefit from our toys and other items, which were still in excellent condition, I found a kindergarten for visually impaired children near our home. Suddenly, my perspective about how toys can be used changed; I closed my eyes and started touching the items to feel how these children would perceive them. I started to focus on sending the kindergarten audio books and textured toys.

An eye opener

Visually impaired children, like other children, may be orphaned, fragile, have elderly parents, are afflicted with diabetes or seizures, or they may be blessed with understanding and educated parents.

I decided to take our children to visit the kindergarten to expose them to all types of children. At the beginning, it was not easy for my children, but then there was a sense of transformation, from sadness or empathy to a desire to help and be of use, to alleviate some of the difficulties facing these children and their parents.

I decided to sort the toys once again to make them of more use to blind kids. I started visiting the kindergarten and organizing many activities with the children in cooperation with volunteers. We organised cooking classes with Chef Mira Jarrar who researched and developed her class to ensure that it was suitable for the visually impaired. One dentist designated one day a week to read to these children–this was a true source of inspiration for me!

The connection

Years passed and our son Saif continued to connect with the children. When the time came for his tenth-grade personal project, he chose to record audio books for visually impaired children in cooperation with his school and a number of his peers who volunteer to read and record.

Five stories were professionally recorded, but when the time came to read them to the children it was vacation time, and then the kindergarten was shut down; like other small projects, it was difficult to sustain.

Saif reached out to one of kindergartens’ former principals, also a visually impaired person herself and a holder of a PhD Degree, to obtain feedback on the recordings. She connected him to several of the children’s mothers who expressed great interest, especially a lady by the name of Um Hashem.

Um Hashem coordinated with the other mothers, siblings and caregivers of the blind children and arranged for a visit to the Children’s Museum in Amman- although many of the children were residents of Zarqa. The Museum proceeded to host our activities.

Engagement

The first activity held at the Children’s Museum Library was a simple one; Saif played the audio stories through a computer. The visually impaired children loved the stories. They were just like a dry sponge absorbing water; the children understood every word; they were overjoyed and laughed at every funny event in the story. This is how we chose the name “Basira” for our initiative, which translates into “insight” or “vision”.

I received many calls from friends and colleagues who learnt about this activity and wished to help. I then created a WhatsApp group to coordinate activities. We consulted and researched similar projects relevant to edutainment. We continue to use Um Hashem and Hashem as a sounding board to test the stories and hear their opinions on the samples of recordings by the volunteers. Hashem exhibited great intelligence and knowledge of the Arabic language; his opinions on the stories significantly improved the quality of our recordings.

During Hashem’s fifth grade exams, Um Hashem sent pictures of her son’s lessons to the WhatsApp group of volunteers. The volunteers, using a free app on their phones, recorded the lessons and explained them to the extent possible, and sent them for auditing and quality assurance. Um Hashem then sent the recordings to Hashem’s classmates for their reference and use.

The volunteers’ enthusiasm was channeled into coordinating and organising records of the curricula of grades one to ten. The data was then uploaded into specialised programmes. With Um Hashem’s support, the Higher Council for the Rights of Persons with Disabilities was contacted. The Council expressed support, announced the blessing of Mired and published all the recordings on its official website. It is noteworthy that Basira’s recordings inspired one individual to reproduce the curricula in sign language, also published on the Council’s website.

Taking it to the next level

Um Hashem and Hashem were a constant source of inspiration for the initiative. Um Hashem then introduced me to Hiba ‘Abbadi- a recent graduate who empathised with the challenges facing visually impaired university students due to the shortage in recordings of the curricula.

In coordination with the university’s administration and after obtaining the approvals necessary for using the audio library, ‘Abbadi succeeded in recording all the curricula of the humanitarian faculties, coordinating 250 volunteers from the university through the Voicrill initiative, which also printed the curricula in Braille.

Meeting ‘Abbadi was a pivotal point for Basira: she reinforced the belief in the ability to achieve big goals through persistence and determination, and more importantly, the transfer of technical knowledge on the details involved in recording, linguistic auditing, electronic archiving, and legal referencing to ensure no copyright infringement took place. The networking with similar projects is a main reason for developing the work, avoiding mistakes, and continuous learning from accumulated experiences.

Basira is now continuously searching for similar projects in the Arab World, also offering facilities to the visually impaired, by printing educational materials in Braille along with sound recordings of stories and curricula for university students. Basira also reached out to stakeholders to brainstorm ideas to facilitate recordings by volunteers with reasonable quality using mobile phones, without the need for a professional recording studio.

Take home message

Basira showed us that volunteerism is rewarding for the volunteers as it proves rewarding for the beneficiary. Helping one another brings joy and elevates the sense of humanity. We also learned that volunteering time and effort is more important than financial assistance in most cases and is needed in all phases and not subject to a specific timeline. The initiative’s success is founded on the efforts of the volunteers as well as the coordination, follow-up, archiving, quality assurance and other tasks that require a firm belief in the work’s benefits.